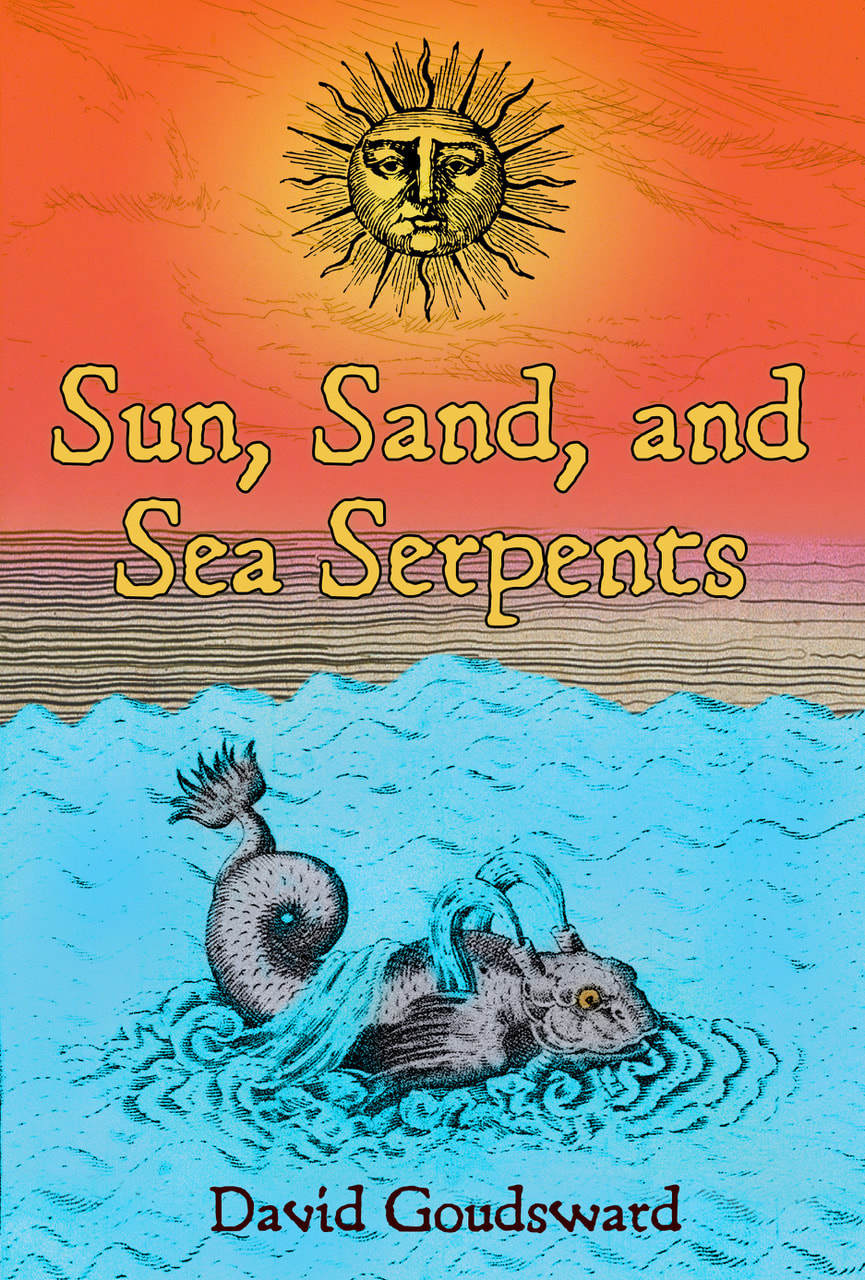

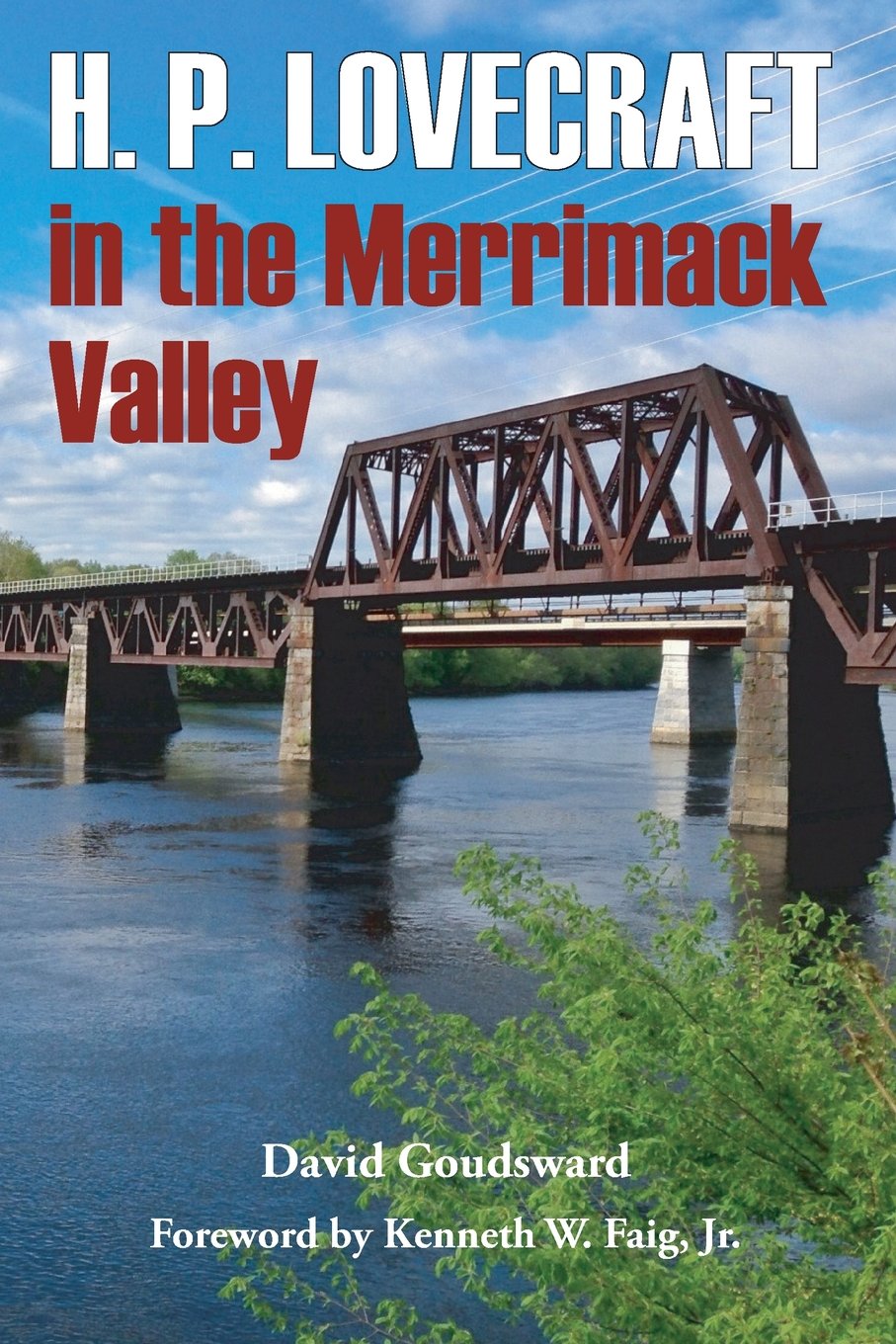

What gave you the idea for “The Vampire in Winter?” The basic concept is what happens if a vampire just gets bored. Some go Goth and shave their heads. Others pretend to be aristocrats. This particular fellow amuses himself by tormenting a vampire hunter he actually has some fondness for. And part of the amusement to our vampiric narrator is that he’s actually telling the priest that the standard tools and techniques are just pop culture nonsense. When did you know you wanted to become a writer? I’ve always been one and have not, apparently, strayed far from my roots. My first publication was a Halloween poem in the first grade for the elementary school newspaper back in 1967. I was amazed that they used it. I distinctly recall hating the ending, which, although rhyming, felt forced. So, 50+ years later, the “self-loathing of published work” part never changed either. Under your real name, you have compiled an impressive collection of horror guides, accounts of Lovecraft’s travels and correspondence, plus some cryptozoological reference material. It’s staggering. How did you get drawn into documenting so many diverse and obscure things? In my head, they’re all related, sort of a unified-brain theory. During college, I interned for a marketing firm that had America’s Stonehenge as a client. To make a very long story short, I ended up managing the site’s tourism side. I also indulged in historical research of the hill’s past (my major was American Studies, specializing in local history). That evolved into my fringe archaeology books/articles on ancient New England locations with alleged pre-Columbian European visitors. While I was at America’s Stonehenge, the first NecronomiCon was held in Danvers, MA. We had a spate of tourists drive up to see the “sacrificial table” described by Lovecraft. As a local historian and a fan of his work, I was appalled that Lovecraft had been to the site, and no one really knew much about it. He had been in my own hometown repeatedly, and there was no actual research as to why or when. That brought me into Lovecraft studies and my first book on the topic, his visits to the Merrimack River Valley. I was already a horror movie fan (Creature Double Feature on Channel 56). So regional horror guides seemed a natural progression, with Poe and Lovecraft having roots in New England. Moby-Dick, admittedly a ponderous read, opens in Massachusetts and has a black magic ceremony and supernatural allegories. And Collinsport, Maine exteriors were actually filmed in Connecticut. How can you not want to share such bizarre overlaps of film settings, filming locations, and literature? You sometimes collaborate with your brother, Scott Goudsward. How do you do this without killing each other? Scott’s survival can be credited entirely to geography. He lives in Massachusetts, and I’m in Florida. I am also too cheap to buy an airplane ticket and fly 1200 miles to kill him. Technology has also helped. Discussions on content and the editing process has become much easier with Facebook’s Instant Messenger and Dropbox. I do not miss the inherent irritation of transferring material on dial-up via AOL IM, compounding the usual fraternal homicidal urges. What are you currently working on? I am all over the map right now, literally and figuratively. I am wrapping up Adventurous Liberation: Lovecraft in Florida, looking at Lovecraft’s three trips to the Sunshine State. I hope to get that one out this year. Scott and I are about halfway through Horror Guide to Southern New England, which will complete the series. I’ve started work on my second book on sea serpents, covering the Canadian Maritimes down to the reports from the mid-Atlantic. I’ve just contracted to revise and update one of my earlier books, Ancient Stone Sites of New England.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Welcome!

Mystery and Horror, LLC, is an indie press interested in what the name suggests. Contact us at: [email protected]

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed